Bowness History

Bowness is an ancient town which has its origins in the eleventh century, when the area was colonised by the invading Norsemen.

Bowness is an ancient town which has its origins in the eleventh century, when the area was colonised by the invading Norsemen.

The area saw rapid expansion in the Victorian era, with the advent of the railways, the establishment of which was staunchly opposed by the poet William Wordsworth, who was concerned that the influx of visitors would spoil the natural appeal of the lake. Many of the town's large hotels were erected to accommodate the rapidly increasing numbers of tourists descending on the area.

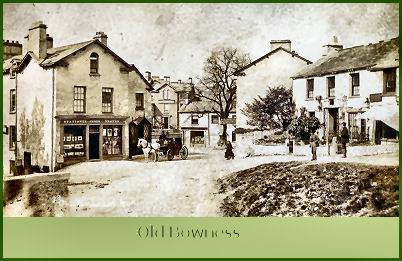

Much of the town we see today dates from the Victorian and Edwardian eras, but parts of the original village survive. The Bowness Rectory dates from the fifteenth century and is the oldest inhabited building in the area. Around it clusters what remains of the older section of Bowness. The above picture dating from circa 1865, depicts Laurel Cottage on the right, the original Windermere Grammar School, which dated from 1613. In the middle distance stands the Royal Hotel. The Deborah Ash, said to have been planted in 1631, by a Phillipson of Langholm to mark the site where a border raider fell, is visible centre-right of the photograph.

The Hole in't Wall is reputed to be the oldest tavern in Bowness, it derives its name from the small window through which ale was once passed to servants watching over their masters' horses outside in the yard. It was the setting for Charles Dickens' narrative, "The Champion Wrestler of All England." The Royal Hotel, once known as the White Lion was patronised by William Wordsworth and is mentioned in his poem 'The Prelude'.

Lake Windermere froze for six weeks in 1895, when people actually walked across it. Other years when the lake was frozen were 1929. 1947 and 1963.

Lake Windermere froze for six weeks in 1895, when people actually walked across it. Other years when the lake was frozen were 1929. 1947 and 1963.

Our thanks to Mr. John Campbell, a native of Bowness, for sharing his memories of a childhood spent in the town with us:-

'Bowness has lots of interesting corners. When I was little, many people still talked about the great freezes at the end of the 19th century. We still used a lot of the old names for places, now largely forgotten. Very few people now know, for example, that Belles Howe, between the Promenade and Windermere Parish Church, now an annexe to the Old England Hotel, stands on what was once a burial ground for the Society of Friends or Quakers. On the Tithe Map, it is listed as a garden. Such a burial ground was usually referred to as a sepulchre and this was no exception, as is told by the local designation of what is now the main road to the bay. We call it Sepulchre Hill, but you will not find this name on any map. When my father was little, it was still a narrow, twisting lane, Sepulchre Lane. The ice-cream shop at the side stretched across what is now the road. You can see it has been cut in half. There was also a well just below there, called the Tenterbeck Well. It was said to have therapeutic qualities. You can still see the mounting stones near the cushion huts for getting on horses.'

'Tenter Beck is one of the little becks running off the fell east of Bowness. Another one is Rattle Beck. Tenter Beck recalls the old cottage woolen industry in Bowness. There were several mills, presumably for fulling the cloth. There is also the site or remains of a spinning gallery at the Spinnery Café (About the position from which the picture of Ash Square was taken). It was first glassed in and some years ago absorbed into the building's interior.'

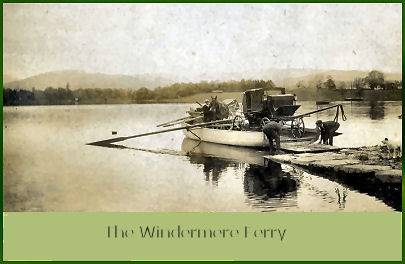

The photograph showing the old ferry depicts the landing stage of which the remains can still be seen facing north just a little further along the nab from the present

landing. The ferry itself was a huge rowing boat. David Wyke, just by Snake Holme, was one of my favourite places for revising for exams. I would nose out rowing boat into the reeds until it was hidden and lie in the bottom and study. We adored the lake.'

The photograph showing the old ferry depicts the landing stage of which the remains can still be seen facing north just a little further along the nab from the present

landing. The ferry itself was a huge rowing boat. David Wyke, just by Snake Holme, was one of my favourite places for revising for exams. I would nose out rowing boat into the reeds until it was hidden and lie in the bottom and study. We adored the lake.'

A HISTORY OF BOWNESS

by John Campbell

Origins: an interpretation of the evidenceHe who hath eyes to see, let him see.

The origins of Bowness are lost in antiquity. There is no documentary evidence relating to the village until the Middle Ages, when there is reference to Bulnyspark. Its name appears to mean bull-headland but this is uncertain, for some derive it from boga naess, meaning bow-headland. The name Bowness is the name of several places in Cumbria. Whether it is seen as being of Anglian or Norse origin depends on the earliest form in which it is encountered. And names do not necessarily betoken origins, for names may be changed when others occupy the land.

So propitious is the site of Bowness village, that it must have been a favoured dwelling-place since man first populated Lakeland after the retreat of the ice thousands of years ago. Clearly the first inhabitants laited out a secluded site that was sheltered and well hidden but also offered a good source of food. Even today the oldest part of the village can still be discerned. It is known as Lowside and nestles in a hollow of the land between two low hills. It faces south towards the lake, with a small beck, long covered, running through it. It is hidden from every side. Even from the lake, it is screened by headlands and islands, and remains hidden from view until one has approached it very closely. On the west side is the low rise of New Hall Bank. On the other the land rises sharply to the parish church of Windermere, for Bowness has long been the main settlement in the historically extensive parish that takes its name from the lake included within its bounds. In fact until the arrival of the railway further up the hill in 1848, Bowness and Ambleside were the only two truly nucleated settlements or 'towns' in the whole of the original parish, which stretched from Dunmail Raise in the northwest to Lindeth in the southeast. Everywhere else there were only hamlets and scattered farms. Two narrow streets still thread through the old village, leading down towards the waterfront. They do not reach it, as the way is barred by the Royal Windermere Yacht Club and the Old England Hotel, but there can be little doubt that, centuries ago, they debouched upon the beach where the villagers kept their fishing-boats. By the 17th century Bowness had spread beyond this sheltered hollow on to the broad shelf of land east and north of the church. The Grammar School, now Laurel Cottage, was founded in 1613 on the hillside east of the church, and the Market House was built opposite the church in the 18th century. By the early 19th century the village had filled the flat land and had begun to creep up Cragg Brow, at the top of which the famous chestnut tree was planted in 1815 to celebrate the victory at Waterloo. Here was the gate that lead out on to Undermillback Common and the track leading north into Applethwaite.

The first house built of stone was the Rectory, parts of which date from the 16th century. It lies half a mile south of the village on another south-facing site. It stands on a low rise and has an open view of reed-fringed Parson Wyke and the lowest of the three cubbles into which Windermere is divided. It is a good site for farming and fishing, and is much more extensive than the cramped site of Bowness, but it is both less sheltered and less well hidden. It has uninterrupted views of the hills beyond Bowness and is wide open to the cold northerly winds,. This helps to explain why the village was built on the other bay. Beyond that, we must try to find such evidence as may yet exist to reconstruct the story of Bowness. In the village itself, there is nothing except its site and the pattern of its streets but further north there is more to see. About three miles north of Bowness is perhaps the best viewpoint in the whole district. It is called Allen Knott. It is a name found on hardly any maps, and it is rarely visited. Yet this prominence holds the key to the history of the area. On top of the knott are the barely visible remains of a British 'fort'. It is not very big and probably served chiefly as a lookout post. It has a commanding position, with distant views in an almost 360-degree radius. To the north lies the High Street range. One can look right up the Troutbeck valley and see the ancient track long known as High Street as it comes over the tops from Brougham and then drops down into the valley. Maps mark it as 'Roman' but it is obvious that, while the Romans may possibly have used it and even in part paved it, they did not make it. If they had, it must surely have headed for their fort at Windermere Waterhead. But it does not; and there is no evidence that it ever did, in spite of the dotted line sometimes drawn on maps purporting to indicate a route from the top of High Street and then southwestwards across the shoulder of Wansfell. It has no connexion with Waterhead or with the Roman fort there, for it heads southwards. In the Middle Ages it was known as Brette Strete, the Britons' Road and a glance at an Ordnance Survey map will show its true course and destination. Follow it as it drops down into Troutbeck, runs under the east side of the Tongue, and then follows the east side of the valley for about three miles to rise again up the valley side, crossing the road that snakes up out of Troutbeck towards Garburn and apparently ending at a junction with the by-road from Ings to Troutbeck. It ignores Troutbeck Park farm, passing it at some distance; it runs by the side of Long Green Head but does not form a link between there and any other site inhabited today; and although it crosses the Garburn road, it does not seem to interact with it. There is no true junction: it is inconceivable, for example, that one would turn from one on to the other in any direction. In other words, its route is singularly directed without regard to any of these features of the map. Why then should it end on a little used road up on a fellside away from any habitation? If one goes there, the answer becomes clear; for on the opposite side of the road is the summit of Allen Knott, for which this track clearly aims, still a recognized right of way after at least two millennia, long after its origins have been forgotten, an amazing example of continuity in the landscape.

Return now to Allen Knott and look around. Westwards lies the parallel ranges of the Furness Fells, with the Coniston Fells on the skyline. North of these lie the Langdale

Fells and between the two you can see right into the gap of Wrynose. Further round again are the Rydal Fells and then the dip of Kirkstone Pass, the summit of which is

hidden, before the land rises again to High Street. Turn your back to Wrynose and look southeastwards along the route towards Ings. Six miles beyond, the land falls away

from view, where it drops into the valley of the Kent. This is the same road, no doubt, that leads across Troutbeck and then along Skelghyll Lane to Waterhead, continuing

along the valley of the Brathay and across Wrynose and then Hardknott Pass to the sea at Ravenglass. This, too, is usually said to have been a Roman road, but, on the

evidence of the other, it probably predated them.

Return now to Allen Knott and look around. Westwards lies the parallel ranges of the Furness Fells, with the Coniston Fells on the skyline. North of these lie the Langdale

Fells and between the two you can see right into the gap of Wrynose. Further round again are the Rydal Fells and then the dip of Kirkstone Pass, the summit of which is

hidden, before the land rises again to High Street. Turn your back to Wrynose and look southeastwards along the route towards Ings. Six miles beyond, the land falls away

from view, where it drops into the valley of the Kent. This is the same road, no doubt, that leads across Troutbeck and then along Skelghyll Lane to Waterhead, continuing

along the valley of the Brathay and across Wrynose and then Hardknott Pass to the sea at Ravenglass. This, too, is usually said to have been a Roman road, but, on the

evidence of the other, it probably predated them.

It may be asked with justification why a road should follow the fell-tops to end at a small upland fort. The answer is that it does not, or least did not. It would not make sense for it to have done so. But if one turns one's back on High Street and looks southwards, one's eyes are carried straight down to the islands in the middle of Windermere, and in particular to its largest island known once as Lang Holme but now as Belle Isle after the 18th-century of the Curwens, who came to own it. Indeed from the northern tip of the island, there is a marvellous view, not only of Allen Knott, but up into the Blue Ghyll where the road crashes down off the top of High Street. From Allen Knott, therefore, it is possible to see far along four long-distance routes. It seems unlikely that it was a place of any strength or of refuge but was probably a signalling camp, from which messages could be passed easily if marauders were seen on the horizon, perhaps at other similar camps. It may also have been a place where travellers were required to report and state their business or declare what goods they carried. What course the road may have followed from Allen Knott down to Bowness cannot now be told. It may have gone across the fields, then down the lane to the Kirkstone road and so to Cooks' House Corner, and then along the low road to Bowness. Or it may have been a little further away from the lake.

This discussion seems to have moved far from the origins of Bowness. Yet it is not so. When the foundations for the Round House on the island were being excavated in the 18th-century, parts of a Roman pavement were uncovered. Unfortunately they were then covered up and lost to posterity but it has always been accepted that in Roman times there was a house there. It is often stated, with no apparent evidence, that it was the house of the governor of the Roman fort at Waterhead. It seems much more likely that it was the house of a local magnate, perhaps even the local ruler, controlling the area that later became the parish of Windermere, whether including or not including Grasmere, hidden away behind Loughrigg. He lived on the island; the people lived in the village in the little hollow, where the great road came over the high fells from Brougham and terminated on the north side of the bay. From there, perhaps, boats also set out for the foot of the lake where other tracks led on into Low Furness. Thus two thousand years ago Bowness would have been a small port, where goods were transhipped on the long route across the high fells, as well as the local capital of a wide area around the northern end of Windermere, which would have been 'governed' from the island, whilst another trading settlement also grew up near the fort at the head of the lake, eventually moving up out of the marshy valley on to the hillside north of Stock Beck. This became Ambleside.

It is interesting that this situation still pertained in the 19th century, until the coming of the railway led to the growth of the new town of Windermere. It is also interesting that even today the road north out of Bowness heads for Penrith, not Ambleside or Keswick. The road over High Street fell into disuse long ago, although it is still a wonderful route for the walker. It was replaced by the lower-level route across Kirkstone Pass, now numbered the A592. This crosses the equivalent of the old southeast-northwest road, the A591, at Cooks' House Corner and heads north to Kirkstone Pass. Like its predecessor, it has no real junction with the A591. No village ever sprang up where they cross. It also ignores the several hamlets that follow the line of springs on the west side of the Troutbeck valley. It is joined by a branch from Ambleside, coming up 'The Struggle', and passes through no big villages on its. Only the roadside hamlets of Patterdale and Glenridding lie on its path. Furthermore, just as its predecessor was probably part of a long-distance road and water route between the Eden valley and Low Furness, the A592 continues along the east bank of Windermere to Newby Bridge, where it feeds into the road to Ulverston and Barrow.

It may be argued that the evidence for the great antiquity of Bowness is slim, but it is difficult to envisage any other scenario that explains the facts on the ground and the map: the great road, the fort, the pavement. And this, if it be true, leads to further possibilities. For, if Bowness was an established and locally important place two thousand years ago, then is it not likely that it would also have been a local religious centre? The churchyard is surrounded by yew trees of indeterminate age but the present church was built at the end of the 15th century, when the old one was destroyed by a fire. Part of the old one can be seen at the base of the tower. It is usually said to date from pre-Norman, Anglian times. Perhaps it is older, or stands on an older site. Cumbria received Christian influences at an early date. Missionary active in the north is well known but in the south it is much more sketchy, in spite of recent claims for the antiquity of religious activity in Urswick. In the north, the earliest name to stand out is that of St Ninian. At Brougham there is a tiny church dedicated to this saint, who may have preached there. It is called in the local fashion Ninekirk. This church lies very near the northern end of the great road across the high fells. Windermere Parish Church, in Bowness, lies at the other end. It is dedicated to St Martin, the man who was Ninian's friend and inspiration. Is it just possible, then, that this dedication reflects early contacts along this road or even a visit by Ninian himself to the shores of Windermere? Shall we ever know? Probably not: not, that is, unless new documentary or archŠological evidence comes to light; and so we must just try to interpret the evidence in the best way we can, always being careful to distinguish between facts and possibilities.